The Most Important Graph You’ve Never Heard About

~500 words. 2.5 minute read.

Have you ever thought about how much can go wrong when flying on an airplane after seeing news about a plane crash? Recency bias. Ever had a hard time parting with something you built with your own hands? IKEA effect. Anchoring, representativeness, Halo-effect - there’s a lot of these. But there’s a lesser-known one that really packs a punch:

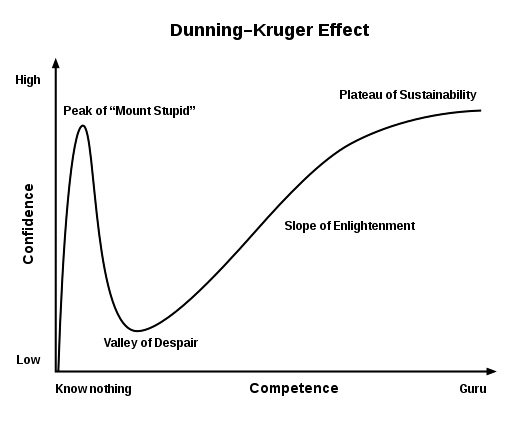

The Dunning-Kruger effect, as it is now known, describes the cognitive bias under which people assess their competence to be greater than it actually is, especially if their competence is low. For instance: What do you really know about the nuclear deal with Iran?

Conversely, the more you know about something, the more you realize that there is a lot that you don’t know. You recognize that there is a lot to learn before you can claim any sort of expertise (how much have you really read about the nuclear deal with Iran?). Therefore you tend to underestimate your competence in that particular field.

Frequently, this bias is expressed in a graph that looks something like this:

Dunning and Kruger published their study in 1999, but it is worth bringing it back to the center of our collective attention today. Why?

It is easier now than ever before to ride a wave of ‘authority’ when at the top of ‘Mount Stupid’ and make declarations in an un-nuanced, self-unaware (if that’s a word) manner, typically using 280 characters (preferably less for even more impact, according to one Twitter-study).

“If you’re honest, you don’t have the authority to speak on most topics, you just think that you do.” said a friend of mine (a true connoisseur of the Dunning-Kruger effect). The ‘you’ here is obviously ‘everyone’.

I remember how a professor of mine outlined the knowledge journey using this graphic:

To summarize: The more you know, the less you know. There are many great side-effects to this though: Humility, the ability to identify and articulate nuances, and explaining the situatedness of an argument within a broader context. This narrows the frame of the problem and produces solutions requiring fewer dependencies.

A paradoxical result of the Dunning-Kruger effect is that those who are on top of ‘Mount Stupid’, with high confidence but low competence, are louder, more visible, and more assertive than those who are more competent. And that is what we observe when browsing our Twitter feed.

Within this context, the Twitter problem has nothing to do with free speech or ownership. It has everything to do with enabling the worst societal dynamics the Dunning-Kruger effect has described.

I found it useful and eye-opening to ask myself: Where on the Dunning-Kruger curve do I fall on any given topic? Where do others? These can be behavior-changing questions.

I hope I knew just enough to post this.